Makedonlar

| Toplam nüfus | |

|---|---|

| 2,000,000 - 2,500,000[1] | |

| Önemli nüfusa sahip bölgeler | |

| 1,297,981[2] | |

| 83,978-200,000[3][4] | |

| 78,090[5] | |

| 62,295-85,000[4][6] | |

| 61,304-63,000[4][7] | |

| 51,891-200,000[4][8] | |

| 45,000[9] | |

| 37,055-150,000[4][10] | |

| 31,518[11] | |

| 30,000[9] | |

| 25,847[12] | |

| 13,696-15,000[4][13] | |

| 10,000-15,000[4] | |

| 11,623[14] | |

| 9,000[4] | |

| 7,253[14] | |

| 5,071-25,000[15][16] | |

| 4,697-35,000[17] | |

| 4,600[18] | |

| 4,270[19] | |

| 3,972[20] | |

| 3,669 - 15,000[4][21] | |

| 3,419[22] | |

| 3,349-12,000[4][23] | |

| 3,045[24] | |

| 2,300-15,000[25] | |

| 2,278[26] | |

| 2,000-4,500[27][28] | |

| 1,000[27] | |

|

962 (2001) 10,000-30,000 (1999 tah.)[29] | |

| 819[30] | |

| 731-6,000[31] | |

| Diller | |

| Makedonca | |

| Din | |

| Ortodoksluk, İslam, Protestanlık | |

| İlgili etnik gruplar | |

| Torbeşler | |

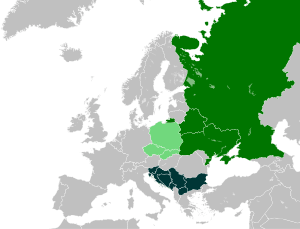

Makedonlar (Makedonca: Македонци - Makedontsi), Balkan Yarımadası'nda çoğunlukla Makedonya Cumhuriyeti'nde yaşayan bir Güney Slav etnik grubudur. Güney Slav dili olan Makedoncayı konuşurlar. Makedon etnik unsurunun yaklaşık üçte ikisi Makedonya Cumhuriyeti'nde yaşar.Ancak diğer ülkelerde bir dizi topluluklar da vardır.

Orijin

Makedonların "kökenleri" çeşitli ve zengindir. Antik dönemde merkezi Aşağı Strymon olan, Kuzey Makedonya'daki Vardar havzasında Paionyanlar tarafından iskan edildi. Pelagonesler, Pelagoniyenye'de Yukarı Makedon halkları tarafından iskan edildi; batı bölgesinde iken İlirya (Ohri-Prespa) halkları tarafından iskan edildiği söyleniyordu.[32] Geç Klasik Dönemde, madenciliğe dayalı birçok gelişmiş polis tipi yerleşim vardı ve bunun yanında ekonomi gelişiyordu.[33] Bu gelişim sayesinde Paeonia, Makedonya Krallığı'nın kurucu eyaleti oldu.[34] Roma'nın bölgeyi fethiyle Romalılaşma başladı. Bu Romalılaştırma bölge üzerinde kalıcı bir etki bıraktı.[35]

Antropolojik olarak Makedonlar, Balkanlarda tarih öncesi ve tarihi demografik süreçleri temsil eden genetik soya sahiptir. Bu tür soy da genellikle diğer Güney Slavları olan Bulgarlar, özellikle, Sırplar, Boşnaklar, Karadağlılar ve aynı zamanda kuzey Yunanlar ve Romenler bulunur.

Kimlik

Makedonların büyük bir çoğunluğu bir Slav dili konuşur, kendilerini Ortodoks Hıristiyanlar olarak tanımlayarak komşuları ile kültürel ve tarihsel "Ortodoks Bizans-Slav mirası"nı paylaşır.

"Makedon" etnik köken kavramı, Ortodoks Balkan komşuları tarafından farklı bir etnik olarak görülmektedir.[36][37][38][39][40][41] Bu Makedon kimliği, 19. yüzyılın sonlarında ortaya çıktı ve bu 1940'larda Yugoslav devlet politikasına dayandırıldı.[42][43][44][45][46] Ancak modern araştırmacılar dünya üzerindeki varlığını sürdüren bütün ulusların modern yapılar olduğunu bilmektedir. Uzun geçmişe ile etnik gruplar, Romantik Milliyetçilik hareketi sırasında 'antik geçmiş' ve 'yeniden icat' dönemi yaratmak istediler.

Ortaçağ boyunca farklı bir etno-politik Makedon kimliği vardı.

Ayrıca bakınız

Kaynakça

- ↑ Nasev, Boško (1995). Македонски Иселенички Алманах '95. Skopje: Матица на Иселениците на Македонија. s. 52 & 53.

- ↑ 2002 census

- ↑ 2006 Census.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Population Estimate from the MFA.

- ↑ Foreign Citizens in Italy, 2007.

- ↑ 2006 figures.

- ↑ 2005 Figures.

- ↑ 2007 Community Survey.

- 1 2 Nasevski, Boško (1995). Македонски Иселенички Алманах '95. Skopje: Матица на Иселениците на Македонија. s. 52 & 53.

- ↑ 2006 census.

- ↑ 2001 census.

- ↑ 2002 census.

- ↑ 2001 census - Tabelle 13: Ausländer nach Staatsangehörigkeit (ausgewählte Staaten), Altersgruppen und Geschlecht — p. 74.

- 1 2 1996 Estimate.

- ↑ 1.2001 Bulgarian census data.

- ↑ Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe, Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE) - "Macedonians of Bulgaria".

- ↑ http://www.fes.hr/E-books/pdf/Local%20Self%20Government/09.pdf Artan Hoxha and Alma Gurraj "LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT AND DECENTRALIZATION: CASE OF ALBANIA. HISTORY, REFORMES AND CHALLENGES" "...According to latest Albanian census conducted in April 1989, 98% of Albanian population are Albanian ethnic. The remaining 2% (or 64816 people) belong to ethnic minorities: the vast majority is composed by ethnic Greeks (58758 ); ethnic Macedonians (4697)...",, Joshua Project.

- ↑ OECD Statistics.

- ↑ 2002 census.

- ↑ 2002 census.

- ↑ 2006 census.

- ↑ "Belçika nüfus istatistikleri". www.dofi.fgov.be. 2 Mayıs 2009 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. http://web.archive.org/web/20090502070847/http://www.dofi.fgov.be:80/fr/statistieken/statistiques_etrangers/Stat_ETRANGERS.htm. Erişim tarihi: 2008-06-09.

- ↑ 2008 census.

- ↑ 2008 figures.

- ↑ 2003 census,Population Estimate from the MFA.

- ↑ 2005 census.

- 1 2 Makedonci vo Svetot.

- ↑ Polands Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947, p. 260.

- ↑ "Greece – Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (along guidelines for state reports according to Article 25.1 of the Convention)". Greek Helsinki Monitor (GHM) & Minority Rights Group – Greece (MRG-G). 1999-09-18. 20 Şubat 2009 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. http://web.archive.org/web/20090220153258/http://dev.eurac.edu:8085/mugs2/do/blob.html?type=html&serial=1044526702223. Erişim tarihi: 2009-01-12.

- ↑ Montenegrin 2003 census -.

- ↑ 2002 census.

- ↑ A J Toynbee. Some Problems of Greek History, Pp 80; 99-103

- ↑ The Problem of the Discontinuity in Classical and Hellenistic Eastern Macedonia, Marjan Jovanonv. УДК 904:711.424(497.73)

- ↑ A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley -Blackwell, 2011. Map 2

- ↑ Macedonia in Late Antiquity Pg 551. In A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley -Blackwell, 2011

- ↑ Krste Misirkov, On the Macedonian Matters (Za Makedonckite Raboti), Sofia, 1903: "And, anyway, what sort of new Macedonian nation can this be when we and our fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers have always been called Bulgarians?"

- ↑ Sperling, James; Kay, Sean; Papacosma, S. Victor (2003). Limiting institutions?: the challenge of Eurasian security governance. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. s. 57. ISBN 978-0-7190-6605-4. "Macedonian nationalism Is a new phenomenon. In the early twentieth century, there was no separate Slavic Macedonian identity"

- ↑ Titchener, Frances B.; Moorton, Richard F. (1999). The eye expanded: life and the arts in Greco-Roman antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press. s. 259. ISBN 978-0-520-21029-5. "On the other hand, the Macedonians are a newly emergent people in search of a past to help legitimize their precarious present as they attempt to establish their singular identity in a Slavic world dominated historically by Serbs and Bulgarians. ... The twentieth-century development of a Macedonian ethnicity, and its recent evolution into independent statehood following the collapse of the Yugoslav state in 1991, has followed a rocky road. In order to survive the vicissitudes of Balkan history and politics, the Macedonians, who have had no history, need one."

- ↑ Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war. New York: Cornell University Press. s. 193. ISBN 0-8014-8736-6. "The key fact about Macedonian nationalism is that it is new: in the early twentieth century, Macedonian villagers defined their identity religiously—they were either "Bulgarian," "Serbian," or "Greek" depending on the affiliation of the village priest. ... According to the new Macedonian mythology, modern Macedonians are the direct descendants of Alexander the Great's subjects. They trace their cultural identity to the ninth-century Saints Cyril and Methodius, who converted the Slavs to Christianity and invented the first Slavic alphabet, and whose disciples maintained a centre of Christian learning in western Macedonia. A more modern national hero is Gotse Delchev, leader of the turn-of-the-century Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which was actually a largely pro-Bulgarian organization but is claimed as the founding Macedonian national movement."

- ↑ Rae, Heather (2002). State identities and the homogenisation of peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. s. 278. ISBN 0-521-79708-X. "Despite the recent development of Macedonian identity, as Loring Danforth notes, it is no more or less artificial than any other identity. It merely has a more recent ethnogenesis – one that can therefore more easily be traced through the recent historical record."

- ↑ Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. s. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6. "Unlike the Slovene and Croatian identities, which existed independently for a long period before the emergence of SFRY Macedonian identity and language were themselves a product federal Yugoslavia, and took shape only after 1944. Again unlike Slovenia and Croatia, the very existence of a separate Macedonian identity was questioned—albeit to a different degree—by both the governments and the public of all the neighboring nations (Greece being the most intransigent)"

- ↑ Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, 1995, Princeton University Press, p.65, ISBN 0-691-04356-6

- ↑ Stephen Palmer, Robert King, Yugoslav Communism and the Macedonian question,Hamden, Connecticut Archon Books, 1971, p.p.199-200

- ↑ The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939–1949, Dimitris Livanios, edition: Oxford University Press, US, 2008, ISBN 0-19-923768-9, p. 65.

- ↑ The struggle for Greece, 1941–1949, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1-85065-492-1, p. 67.

- ↑ Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton,Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1995, ISBN 1-85065-238-4, ISBN 978-1-85065-238-0, p. 101.

Dış bağlantılar

- New Balkan Politics - Journal of Politics

- Macedonians in the UK

- United Macedonian Diaspora

- World Macedonian Congress

- House Of Immigrants

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||